There is a boy.

Like you, Céfiro, this boy is almost a man. But he does not live in our time. He lives long before the storm, in a land that is far from here.

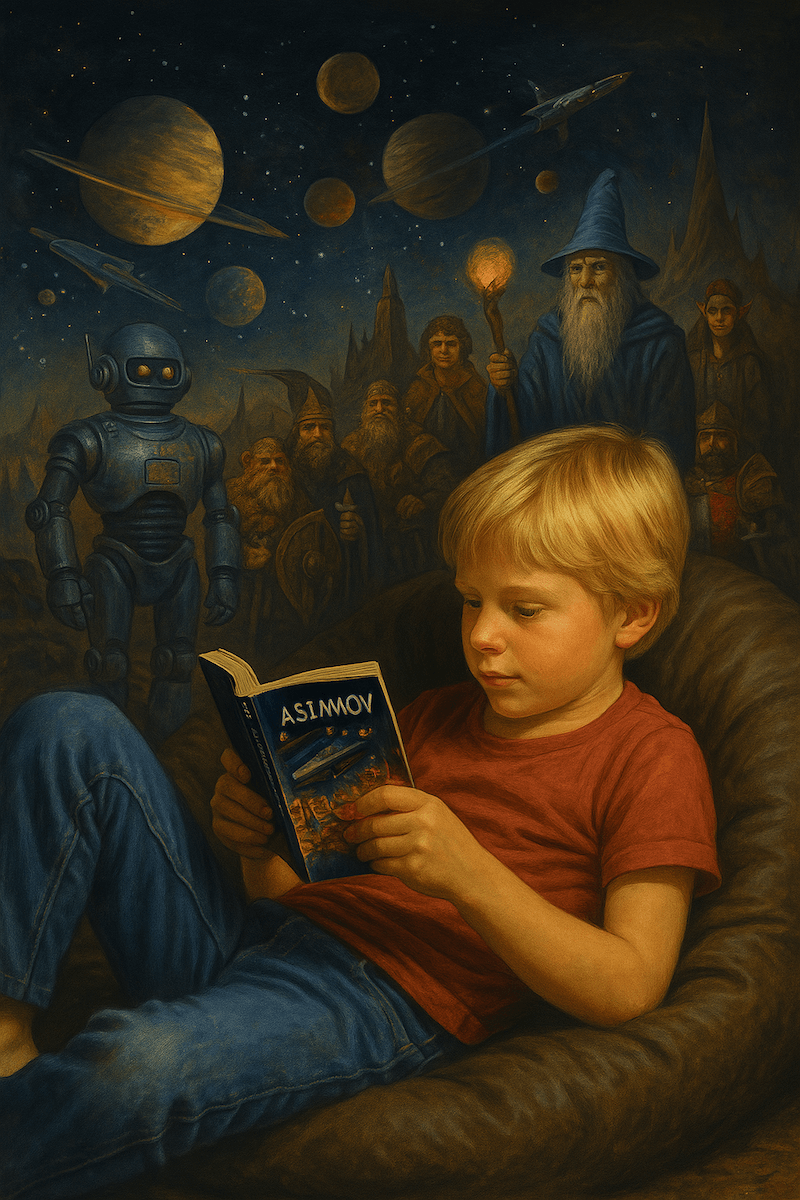

His name is Pedro, and like you, Emma, he is innocent and soft-hearted. One day, Pedro is lost in his books when he notices a little brown mouse emerge from a hole in his bedroom wall. Unlike most mice, this one does not run away when he approaches it. Instead, it runs in circles, limping and stumbling, and Pedro sees that its leg is badly hurt.

Pedro wants to help, but he is worried that the mouse will bite him, so he brings his father’s glove, and puts it on when he picks up the injured mouse. The mouse is worried, too, and it does try to bite him, but the glove is too thick for its little teeth. Pedro puts the mouse inside a box and places it on his desk.

He calls the mouse Ositito, because it is so furry that it looks like a tiny little bear.

“Do not worry, Ositito,” Pedro says. “We are friends now. I will not hurt you.”

Pedro’s father is a hard man, but he loves his son, and he worries much about his future. They are a high-born family, with a good name, but they are also poor.

“All of his brothers are strong,” he tells Pedro’s mother that night as the family eats their evening meal. “They will make fine soldiers. But Pedro? What will he be? A blacksmith? A field hand?”

“That would be a disgrace!” his mother says.

“I will be a soldier too!” Pedro says.

“You would not last a year,” his father grumbles, but then he sees the shame on his son’s face.

“You are as strong as any of your brothers,” he tells Pedro. “Even Gomez, perhaps. But you are soft of heart.”

“I am not!” Pedro says.

“I saw you slip some rice in your pocket,” his brother Gomez says, and his voice is loud, because his father’s words have made him jealous. “Have you found another wounded bird?”

Pedro says nothing for a moment, for he is embarrassed.

“Well?” his father asks.

“A mouse,” Pedro whispers.

Gomez laughs, and Pedro’s other brothers laugh too, until they see the stern look on their father’s face, and grow silent.

“You will be a priest,” his father says, patting Pedro’s shoulder. “And a worthy one.”

But Pedro knows that his father is disappointed in him, and that night he cries to his new friend Ositito.

“I wish that I, too, was fierce,” he whispers to the mouse. “There is no glory in being a priest.”

Later, in the darkness of a new moon, Pedro dreams that he meets an old man.

The man is very, very thin, except for a bulging belly. His face is so thin that Pedro can see the bones in his chin and cheeks. The man has very dark skin and deep, burning eyes that look like smoldering bits of coal.

“Are you a ghost?” Pedro asks.

“No,” the man says. “I am a god.”

“That is not possible,” Pedro says.

“Why not?”

“There is only one god. You must be a demon.”

“I am not your god,” the man says. “But I am a god, nonetheless.”

“Why do you trouble my dreams?” Pedro asks.

“You are no longer dreaming,” the man says.

Pedro looks around and realizes that this is true. He was dreaming, he is sure of that, but now he is sitting up in his bed, and the house around him is quiet, and the man is standing in the middle of his bedroom.

“What do you want?” Pedro asks, and he hears that his own voice is sharp with fear.

“I have a gift for you,” the man says. “If you want it.”

Pedro is confused, for the man’s hands are empty.

“What gift?” he asks.

The man leans close, and the smell of damp earth fills Pedro’s nostrils. It is the smell of a hole in the ground, freshly dug, and yet to be filled.

“Cruelty,” the man whispers. “That is the only thing you lack.”

“Cruelty?” Pedro cries. “I do not want it!”

“No, but you do want everything that will come with it.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean glory!” the man says. “A life of adventure. Beautiful women falling at your feet. Riches you cannot imagine.”

“What does cruelty have to do with these things?” Pedro asks.

“As I said, it is the one quality that you do not have. You are exceptional in every other way.”

“Still, I do not want it,” Pedro says again, but his voice is a whisper now.

“Is it really desire you lack? Or is it courage?”

“Go away,” Pedro says.

“I will. But I will come to you again, and I will offer you my gift one more time. If you refuse it a second time, you will never see me again.”

Pedro blinks, and he finds himself alone in his room.

He goes to his desk, and looks into the box where he keeps Ositito.

“What a strange dream, little mouse,” he whispers, and gives Ositito another pinch of rice. “The more so because I do not remember waking.”

***

Over the next few days, Ositito grows strong again, and he stops running around in circles and begins trying to climb out of his box.

“When you are well enough to climb out,” Pedro says, “you will be well enough to leave.”

The mouse allows Pedro to hold him now, for he trusts Pedro, and he likes it when Pedro runs a gentle finger down his back.

Every day, Pedro brings more rice to the mouse, who keeps him company as he sits at his desk studying his Bible, for Pedro has decided to become the most worthy priest that has ever lived, and to bring a mountain of honor upon his father and his family.

But in front of his desk is a small window, and outside, he can see his brothers practicing their soldiery. They leap, and they wrestle, and they fight each other with wooden swords, and sometimes they wave in his direction, and whisper to each other, and laugh.

“Their ridicule is misguided,” Pedro tells Ositito. “I merely walk a different path.”

Yet Pedro is sad, for his brothers look so happy, and his studies are so dull. And inside him, no matter what he says to his pet mouse, shame gnaws at his heart.

A week passes, and then another week, and then a month.

Finally, on the night of the next new moon, the old man with fiery eyes returns in the darkness.

“I accept your gift,” Pedro tells him, although he did not plan to utter these words, and begins to sob as they pass his lips.

“Then it is yours,” the man says, waving his hand and smiling, and Pedro can see that his old, withered arm is covered in black spots, and that he has only a few teeth, all yellow and black.

“What sort of god are you?” Pedro asks.

“You must already know,” the man says.

“Where is my gift?” Pedro asks.

“I have given it to you.”

“I don’t feel any different.”

The old man walks over to Pedro’s desk, and he pulls Ositito from the little box, holding the squirming mouse by its tail.

He hands the mouse to Pedro, who cups his hands to receive it.

“Go ahead,” the man says.

Pedro regards the Ositito for a moment, noting that the mouse seems relieved to be back in his friend’s hands, safe from the repulsive stranger.

Pedro pets Ositito one last time, then he begins to squeeze.

He watches as the mouse’s eyes grow large, and as it struggles to free itself, and he wonders at this new feeling inside his chest, this new fluttering in his heart.

After a moment, the mouse stops struggling, and lies still in Pedro’s hand, and he stares at it, and pets it one last time, and smiles.

***

In the years that follow, Pedro becomes the fiercest among his brothers. Where they once snickered behind his back, they now cower at his feet.

All of them grow into strong young men, trading their dull wooden sticks for steel swords so sharp that they could cut the wind in two, and mastering the art of killing other men.

They become skilled soldiers, and one day they board a ship, and they sail across the ocean to a land of adventure, full of untold riches to claim and bloodthirsty savages to conquer. It is the perfect place for a soldier, and especially for a soldier like Pedro.

In this new land, Pedro shines with such glory that the savages call him Tōnatiuh, the sun god, for he is fair-haired and terrible, and very brave in battle.

In time, Pedro becomes known for his terrible cruelty. Even in an age where cruelty is common, Pedro’s heartlessness strikes dread into those around him, even his friends. For even they do not murder with such glee. Pedro does not just kill warriors in battle, but women—mothers and grandmothers—and even children. Pedro wields his cruelty against all who resist, and against many who do not.

Years pass as Pedro heaps more glory upon himself, and more sin, too. But his dreams are untroubled, for the old man’s gift has wrapped itself tightly around Pedro’s cold, black heart.

Then, one night, again in the darkness of the new moon, the old man returns.

“I was wondering if I would see you again,” Pedro says.

“You may not have seen me, but I have been watching you closely,” the old man says. “You have brought much suffering.”

“You dislike this?”

“No. Suffering, despair, death… these things nourish me.”

“And yet you are still hungry,” Pedro says, for he can see that the old man wants something.

“Yes,” the old man replies.

“Hungry for what?”

“You and your men travel south now.”

“Yes.”

“Soon you will meet a mighty warrior in battle.”

“We have met many such warriors, and we have vanquished them all.”

“None like this one. This warrior is the greatest among all of the people of these lands. He is stronger even than you. Smarter, more skilled in battle, and more courageous.”

Pedro laughs.

“I have hundreds of cavalry with me, and thousands of conscripts. Surely we can best a single savage.”

“This is why I have come,” the old man says. “It is important that you fight this man alone.”

Pedro thinks for a moment.

“I am not afraid of any man,” he says. “But I would know your reason for this.”

“My reason is simple,” the old man says. “If fifty soldiers slay a hero, he becomes a legend. If one man slays that hero, he becomes nobody.”

“You want this man forgotten?”

“Yes,” the old man says. “For I despise him. But I also want to see these people suffer, and I know that if a single man beats their greatest hero, they will despair. They will lose heart, and surrender, and become your slaves. I greatly desire this.”

Pedro is surprised at the eagerness he hears in the old man’s voice. He senses that the old man is concealing something from him, but he does not know what.

“You say that you are hungry for their suffering,” Pedro says thoughtfully. “I, too, have hunger.”

“You seek to bargain with me?” the old man asks, and Pedro sees that the waxen skin of his cheeks has flushed with anger. “After all that I have given you?”

Inside, Pedro trembles, but he tries not to let the old man see the fear in his heart.

“I have won much glory and wealth, it is true. But I wish to rule. I want a kingdom of my own.”

The old man’s laughter reminds Pedro of jackals yelping.

“You will have that, too,” the old man says. “But always remember this: what a god has given, a god can take away.” Here the old man snaps his fingers, and the sound cuts through the night. “Do not try me again.”

“I will fight this man,” Pedro says. “And I will kill him if I can.”

“If you would kill him, you must remember one thing,” the old man says. “To prevail, you must fight him from horseback. If you dismount, or if you are unhorsed, he will defeat you.”

***

Three days later, on a Tuesday, it happens just as the old man foretold. Pedro and his men are met by a great army of savages. As the two groups array themselves for battle, Pedro sees the great warrior.

Though shorter than Pedro, the man’s shoulders are broader, and his head is almost square, so that he looks like a statue chiseled into the rock of a cliff. On his head is a crown, not of gold, but of long, vibrant green feathers.

He is a king! Pedro thinks.

But he is not like any king Pedro has seen before. The kings of his own world are content to fatten themselves upon high, gilded thrones while other men do battle in their name. This man, this savage warrior king, stands at the front of his army, wielding a great spiked club and holding a carved wooden shield.

He is magnificent, Pedro thinks. I will enjoy his death all the more.

Pedro holds up a hand, and his men halt, and he rides out alone into the space between the two armies.

He waves at the savage king, then draws his sword and points it at him. The king understands his challenge, and he waves his warriors away, and he strides forward alone.

When he is close enough for Pedro to hear him, he speaks loudly. Pedro does not understand his language, though, nor does he care to converse, for there is nothing to say. This man must die.

So Pedro puts his sword away and levels his great wooden lance at the king, then spurs his horse forward.

The savage king prepares for his assault, raising his great spiked club. At the moment of impact, he moves swiftly, like a jaguar, turning Pedro’s spear aside with his shield and heaving a mighty blow with his club.

This blow is powerful enough to kill Pedro, even with his thick armor, but it does not find him.

Instead, it finds his horse.

In that instant, as his mount crumbles beneath him, Pedro realizes what has happened, and why the old man told him not to dismount.

This savage king has never seen a horse, he thinks. He believes I am some sort of four-legged demon, and that my horse is part of me.

Before the great warrior can realize his mistake, Pedro leaps from his falling horse and thrusts his lance deep into the man’s chest. The look of surprise on the savage king’s face is something Pedro will never forget, for it makes this victory taste all the sweeter to his wicked heart.

Pedro pulls his lance from the savage king’s chest, and the king falls to the ground, although he is dead before he reaches it.

Now there is no sound except the wind, for the men of both armies are in shock. In this silence, there comes a single sound, the sound, perhaps, of a child crying.

Suddenly, a beautiful bird descends from the sky. Its feathers are long and brilliant green, just like the feathers in the crown worn by the savage king. The beautiful bird lands on the body at Pedro’s feet, and it sits there on the king’s chest, heedless of the blood now soaking its radiant green feathers, and looks up at Pedro.

And for the first time in many years, Pedro feels uneasy. For the eyes of the bird are big and brown, with no white in them at all, very much like the eyes of his old pet mouse Ositito. Pedro is no longer capable of feeling shame, but he begins to feel something else. He begins to feel a sense of doom.

In the years that follow, that feeling grows inside him like a cancer. Even when he gains the kingdom the old man promised him, and rules the lands of the people he has conquered, and vents his terrible cruelty upon them at will, Pedro feels as if he is in a tiny boat being sucked down a river toward a great crashing waterfall.

***

One night, as Pedro lies in his bed, he comes to a decision.

“I must go,” he tells himself. “There are many other savages to conquer, and many other lands that I may bring under my dominion.”

Pedro is speaking to himself, so he is surprised to hear a voice answer him.

“You cannot go,” the voice says, and Pedro turns to see that the old man has appeared in the room next to his bed, just as he did when he was a boy.

“Why not?” Pedro asks.

“Because I forbid it,” the old man says. “If you leave, someone will replace you, and that person will be less cruel.”

“What does that matter?” Pedro asks. “Wherever I go, I will bring death and despair with me. You will have your nourishment.”

“I have it now,” says the old man. “All that I shall ever need.”

Pedro is confused for a moment, for the old man has never forbidden him anything, or told him what he may or may not do.

Except with the savage king, he remembers.

And as he thinks about that battle, he suddenly realizes what the old man was concealing from him that day.

“You once told me that you were someone else’s god,” Pedro says. “I think you are the god of these people. These savages. It is their suffering you require.”

“I am your god, too,” the old man says. “I have been since the moment you accepted my gift. And as your god, I command you to stay.”

“You are not my god,” Pedro says, leaping to his feet, enraged by the old man’s words.

“Am I not?” the old man laughs. “What other god would have you now?”

“You are a fiend!” Pedro says, but his voice is weak, as if he does not find his own words convincing. “Leave me!”

But the old man is already gone, and Pedro will not see him again except once, very briefly, many years later.

For gods are patient, having no reason to hurry. To them, time is of little importance, for in the end they always get what they want.

***

Pedro does leave his kingdom, and he has many adventures, and he even gains a second kingdom, all the while reveling in the old man’s gift of cruelty, all the while spreading pain and horror and death wherever he goes. Perhaps he believes this will satisfy the old man, but as you will see, it does not.

For one day, after a fierce battle, Pedro and his men are returning through a mountain pass when they see the figure of an old peasant standing on the slope above them, looking down at them with an idiot’s smile. Pedro’s men ignore the peasant, who is frail and sickly, but Pedro recognizes his face.

“Kill that man!” he orders, for the sense of doom he has been carrying with him has grown stronger of late, and it lies heavily on his soul.

One of Pedro’s soldiers, a man named Montoya, spurs his horse up the slope, eager to do Pedro’s bidding, even if it is simply to slay a helpless old man. But we know, as Pedro also knows, something that Montoya does not, which is that this particular old man is not helpless, for he is not a man at all.

When Montoya draws near, the old man leans forward and breathes his foul breath into the nostrils of the horse, who, smelling death and decay, becomes terrified. It rears, and it falls backward down the slope, and then begins tumbling toward Pedro and his men. It lands on Pedro, who now tumbles with it down into the creek below.

There, both man and horse come to rest on the rocks. Pedro is on his back, with his face pointed up the slope, where he can see his men scrambling down to help him.

Behind them, forgotten by all, is the old man on the hill.

Forgotten by all, I say, but not by Pedro.

He looks up at the old man, and watches him reach forward, grabbing at something invisible, and pulling it back unto himself, and raising it to his lips, and closing his eyes, and beginning to chew.

The old man chews and chews, with his eyes closed, as if savoring the taste of whatever he is eating. Then he swallows, and he belches.

He has taken back his gift, Pedro realizes, and he finds himself overcome by terror, for above him now is a terrible black cloud.

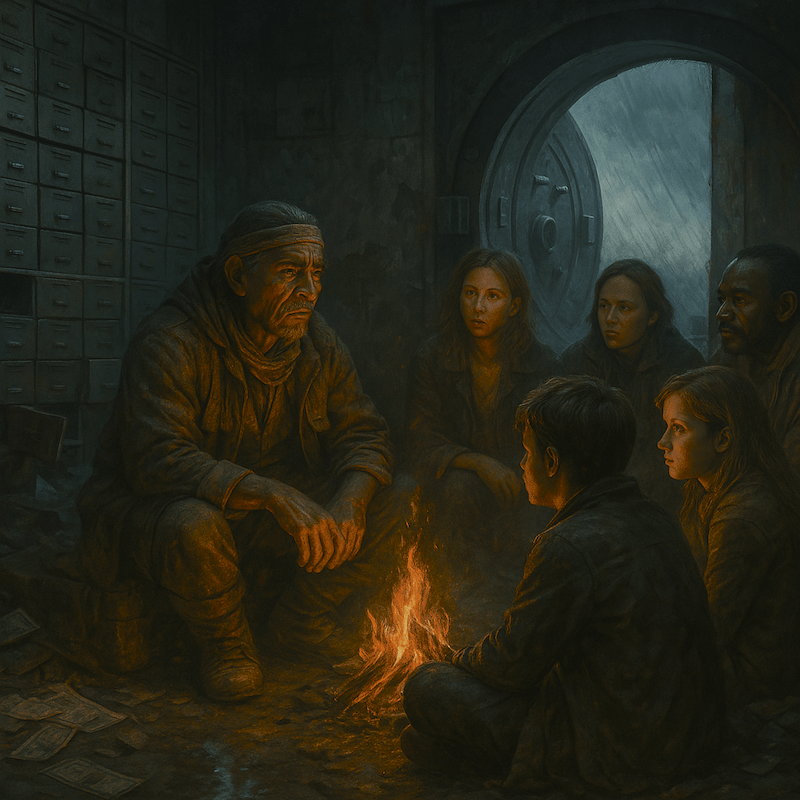

“What pains you, Adelantado?” one of his men asks.

“My soul!” he answers, weeping the tears of a lost child.

For that is what Pedro is. Suddenly, he is no longer the wicked butcher who delights in the slaughter of the innocent multitudes. He is once again the little boy he used to be, whose tender heart moved him to rescue helpless creatures, and nurse them back to health, and give them names, and call them his friends.

Ositito, he thinks, and his heart wails.

But Pedro is also a grown man now, surrounded by an ocean of blood, and he remembers, all at once, every death he has caused, and every small bit of pain he has inflicted, and it feels like there is a mountain sitting on his chest, and a great pit opening up below him, as the faces of all the people he has hurt and killed press themselves into his dying mind. It is more than he can bear, yet bear it he must, for each of these deeds is his own, committed by choice.

For six days he suffers thus, as his men take him to the safety of a nearby village and place him upon a borrowed deathbed, but for Pedro, it seems not like six days but like six lifetimes. His every moment is so filled with anguish and remorse that it seems like no more can fit. Yet more always comes, a constant flood of agony and desolation, until finally, in his last moments of life, he calls out to the old man.

“Make it stop!” he pleads.

And a familiar voice comes to him, although his mortal eyes have failed and he can no longer see anything but darkness.

“Stop?” the voice says. “This has only just begun. For remember, Pedro de Alvarado y Contreras, when you accepted my gift, you took me as your god. My name is Unkameh, the K’iche’ god of death. I rule the darkness of the world below, and it is to that realm that I take you now.”

With that, Pedro dies, and his body is buried in the ground, where it will decompose and disappear, although his soul will have no such luxury.

***

The god Unkameh was right about many things, but he was wrong about one. He said that people would forget the brave warrior king Pedro had slain, the man with the crown of green feathers. Unkameh thought that his name would fade, for usually the voice of the vanquished is a whisper heard by no one. He thought that the warrior king would become nobody, lost to history.

But while the king’s people did eventually surrender, and the death and misery foretold by the old god did come to pass, the warrior king’s name was never forgotten, even today. His name was Tecún Umán, and his people revered his memory for centuries, and they built many beautiful statues of him, one of which stood in the town where I was born. And those same people have come to curse the name of the great white horseman who killed him, the cruel conqueror who some called Tōnatiuh, and who others called Adelantado, but whose mother had named Pedro.

Pedro was the horseman who brought the apocalypse upon the K’iche’ people, but five hundred years later, an apocalypse came for his people, too.

For every great cycle must come to an end, if a new one is to begin.